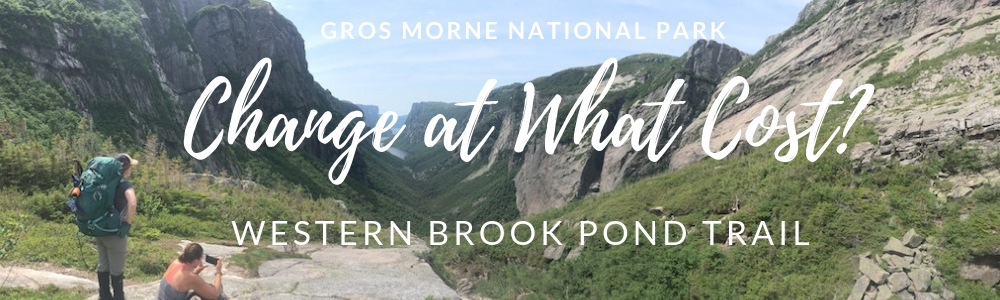

Iconic. Wild. Unmissable.

These are the words that have been used to describe the Western Brook trail and pond experience in Gros Morne National Park.

What is Western Brook Pond?

Western Brook Pond is the jewel of the national park, and a big reason UNESCO named it a World Heritage Site in 1987 – for the park’s “exceptional natural beauty” and “outstanding examples representing major stages of earth’s history”. It’s a 17 km long glacier-cut lake winding its way through 670 meter-high sheer cliffs, and is featured proudly in national tourism ads. Once a salt water fjord, it was cut off from the ocean after glaciers receded 10,000 years ago and the land rebounded.

The trail to the iconic lake has been a highlight for locals and visitors alike. The 3 km nature trail between the parking and lake crosses over the coastal lowland. It has been a favourite introductory-level hiking trail with low, flat grades made up of crushed gravel and boardwalks hovering over the wetland. Up until 2018, this partially forested wetland area contained shaded respite spots. Now the trail as described above has been covered by what can only be described as an access road.

Western Brook Pond, Gros Morne National Park. Courtesy of Tom Cochrane @tomcochrane

Original Trail – Dennis Minty

From Nature Trail to Access Road

I made the discovery of the trail changes in July as I guided a tour group to Western Brook Pond for the much anticipated boat tour of Gros Morne National Park’s famous inland fjord. Throughout the past several years my company has led many tours to experience the nature trail, and the mountain feature at the end of walk. We always get a ton of questions about the wetland plants, so as I parked the van, I silently went over the plants I would try to show them. That turned out to be a futile exercise because what we were greeted by was not a trail, but a gravel road.

Ranging from 4.8 to 6 meters wide in places, the ‘trail’ has at least tripled in width, with gravel the whole way, raised 0.5 meters high from the subgrade. Gone are the boardwalks to protect the ecosystem. The trees which take decades to grow have been plowed over, the delicate and rare plants choked under gravel. We normally allow one hour for the walk so that clients can take photos of the beautiful vistas of the coastal lowlands and highland mountains in the background.

On a sunny clear day with no time constraints, my clients eerily asked no questions about the plants because the tiny surviving orchids were too far away. The raised trail and ditch prevent visitors from getting anywhere near the plants. The classic photo of the irises in the foreground and the dramatic cliffs in the background? Only something you can google now. Nobody stopped for a break in the shade because not a shadow is cast over the trail. Not one person expressed awe at the grandeur of the mountains before them. They simply trudged from the parking lot to the boat dock, and were not interested in the place until we were onboard a boat at the mouth of the fjord. As a guide, former Parks Canada employee, and a local this was a heartbreaking. Local biologist, Michael Burzynski said to CBC Radio: “It is as though we are treading over the grave of a dear friend”.

That day the group completed the trek in a record 25 minutes! The individuals were no more fit or keen than our previous clients, so why were they so fast?

Because the nature trail has been destroyed and replaced by a service road. The nature trail no longer exists. There is no high quality visitor experience allowing people to appreciate nature on what is now an access road to the boat tour. One person put it perfectly: “the prelude to Western Brook Pond has been lost”. This trek won’t be walked for the sake of the hiking experience in itself; it is only being used by people intending on doing the commercial boat tour.

New trail, July 2018

Original Trail. Courtesy of Dennis Minty

New road next to old trail which had connected to wooden boardwalk

Infrastructure Project Details

This $3 million, two-year project started in winter 2017 and will be completed in 2019. Boat tour users accounted for 40,000 of the 2017 trail users. According to the park’s webpage Infrastructure Changes at Western Brook Pond 2017-2019,

With such high visitor appeal, the previous parking lot was frequently beyond capacity, resulting in a public safety concern with large numbers of vehicles parked on the shoulder of Route 430. The trail, with long sections of narrow and sometimes unstable boardwalk, could not accommodate this level of use, causing problems with congestion and creating concerns regarding the safe transportation of fuel and other supplies required for the operation of the boat tour. Some sections of the trail were also prone to flooding, erosion and washouts, necessitating almost daily maintenance.

The project includes:

- An expansion of the parking lot adjacent to Route 430 by 50%.

- Construction of a new off-grid storage building near the parking lot.

- Re-construction of the trail, including a realignment, lowering of grades, and a hardening of trail surfaces to allow for a longer life in our harsh environment, reduced maintenance costs, and the safe transport of supplies such as fuel for the boat tour operations.

- Widening of the trail to allow for multi-use activities (walking, cycling, strollers, wheelchairs, etc.) and emergency vehicle access.

- Replacing the wharf on Western Brook Pond.

- Repairing the boathouse and replacing the building envelope to protect it from extreme winds.

- Dredging of the pond near the boat house to allow for boat storage in early fall when water levels are naturally low.

- These expansions and upgrades will help ensure the quality and reliability of visitor facilities and continue to allow Canadians to connect with nature

Not mentioned here, but stated in the Basic Impact Analysis are also:

- Maintenance of the boathouse winter storage facility will include extending the length of the building to accommodate larger boats

- Upgrading the trail to enable visitors with mobility issues to be shuttled from the parking lot at highway 430 to the Western Brook Pond tour boat dock

New trail 2018. Courtesy of Michael Burzynski

Winter 2017-18 trail work. Courtesy of Michael Burzynski

Loss of Ecological Integrity

Ecological Integrity is a term every ‘Parkie’ soon comes to learn when working with the Parks Canada Agency. It is defined in relation to a park as “…a condition that is determined to be characteristic of its natural region and likely to persist, including abiotic components and the composition and abundance of native species and biological communities, rates of change and supporting processes.”

Basically, a park has ecological integrity when all the components that make up the ecosystem are intact – including physical elements (ie. rocks, water systems), biodiversity (ie. enough abundance of species in an ecosystem), and natural systems (ie. flooding, fire).

The fear is that ecological integrity has been impacted by the construction:

- Levelling, widening of the trail by 4.8- 6 meters, and addition of ditches has killed plants including trees that take several decades to grow in the harsh environment.

- Replacement of wooden walkway with crushed stone will introduce seedlings of common invasive ditch plants, as seen along any logging road in Newfoundland. Plants like black knapweed, coltsfoot, and Canada thistle will choke out orchids, pitcher plant, and sensitive native species.

- This destruction has changed and will further change the ecosystem of animals as the above invasive plants propagate

Dragon's Mouth Orchid of the Western Brook Pond Trail

Caribou feed near Western Brook Pond trail

Above the Law?

As a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the park answers to the World Heritage Programme of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). To keep priorities straight, there are also laws that national parks must follow. Gros Morne National Park falls under several Acts or legislation. These are:

- Parks Canada Act

- Species at Risk Act

- Fisheries Act

- Migratory Birds Convention Act

A cursory look through the first Act I got my hands on, the National Parks Act, raises a red flag. Amongst other things, it states that Parks Canada’s role is:

“to protect the nationally significant examples of Canada’s natural and cultural heritage in national parks (…) in view of their special role in the lives of Canadians and the fabric of the nation” and “to maintain ecological and commemorative integrity as a prerequisite to the use of national parks”

Parks Canada’s own website states that:

“Parks Canada’s objective is to allow people to enjoy national parks as special places without damaging their integrity. In other words, ecological integrity is our endpoint for park management; ecosystem management is the process used to get there”.

Every national park also completes a Management Plan approximately every 5 years, which pares down the future goals of the park. According to their website,

“Gros Morne National Park’s management plan is a strategic guide for future management of the park. It is required by legislation, guided by public consultation, approved by the Minister responsible for Parks Canada, and tabled in Parliament. It is the primary public accountability document for each national park.”

The last Gros Morne National Park management plan was completed in 2009. It contains no mention of the ‘revitalization’ of the Western Brook Pond trail. In fact, a Key Action of the management plan is to “profile Western Brook Pond as a model for sustainable tourism” (p. 31).

Invasive plants introduced via imported gravel choke out sensitive native plants

Has Parks Canada broken the law?

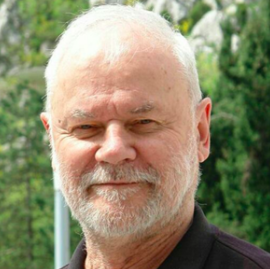

According to Nik Lopoukhine, former Director General of Parks Canada and former chair of the World Commission on Protected Areas, this is very likely. In a CBC Radio interview, he calls the project a “travesty” and states that

“This level of construction would have required a much broader level of assessment in terms of evaluation and input from the people at large. (…) The purpose of the park according to legislation is to maintain ecological integrity. I question whether in fact this has been considered in this particular construction. In fact, I look at it in the context of the environmental assessment, which does not assess any of the implications environmentally. They assess the effects of construction.”

He goes on to say that Gros Morne National Park is a World Heritage Site and a national park. It essentially belongs to all Canadians, so it’s important to involve the public in these decisions and get a sense of what the implications are.

One of the reasons given for the construction project was that visitation was high, leading to constant repair jobs on the old trail. Lopoukhine wonders if perhaps there are too many people frequenting the trail, and if the solution could have been to reduce the number of people on the path.

He also states that visitor experience is very important because “we want people to enjoy the national parks and to value them, but you imagine walking down a gravel road and looking at the devastation on both sides and the changes that have happened… I’m not sure the visitor experience has been enhanced at all.”

Nik Lopoukhine, former Director General of Parks Canada (Society for Ecological Restoration)

It's easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission.

So why’d they do it? A formal Detailed Impact Assessment would take time. And as the saying goes, time is money! Parks Canada has unilateral authority to choose whether they’ll do a Basic Impact Analysis (BIA) or a Detailed Impact Assessment (DIA). If they went ahead with a DIA, there’s a chance that this whole project would be rejected by the public. Someone decided that it would be much easier to push ahead, and explain later. If the public made a fuss after the fact, nothing could be done, and the project would be complete as hoped by those anticipating to profit.

A BIA is for small projects that, according to Parks Canada, “do not generate significant concern from public and stakeholders in relation to potential effects of the project proposal”.

Interestingly, the title of the Basic Impact Analysis for this project is Western Brook Pond Boat Tour Recapitalization – Gros Morne National Park. That title alone points to the intention here. Cashing in on a boat tour at the expense of the environment and at the expense of locals and visitors alike who enjoyed the previous nature trail. It’s now an access road to a privately owned business in a publicly owned park.

Interestingly, the title of the Basic Impact Analysis for this project is Western Brook Pond Boat Tour Recapitalization – Gros Morne National Park. That title alone points to the intention here. Cashing in on a boat tour at the expense of the environment and at the expense of locals and visitors alike who enjoyed the previous nature trail. It’s now an access road to a privately owned business in a publicly owned park.

Take a look at a tiny section at the end of BIA, and you’ll see that one of the collaborators on the analysis actually pointed out that this project could be contravening the Parks Canada Act, which begs the question – why didn’t this raise a red flag to managers and prompt a Detailed Impact Assessment?

BASIC IMPACT ANALYSIS Section 14 Significance of Residual Effects:

Western Brook Pond is an iconic natural feature of Gros Morne National Park which is a designated World Heritage Site. Any residual adverse environmental effects resulting from this project could breech parks Canada’s legal obligation to maintain ecological integrity of this area which has been dedicated to to the people of Canada for their benefit and education, to remain unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations

A Detailed Impact Assessment sounds like it would have been the correct avenue of analysis. According to Parks Canada, it’s the most comprehensive level of assessment and is:

Intended for complex projects that require in-depth analysis of project interactions with valued components; that may affect a particularly sensitive environmental setting or threaten a particularly sensitive valued component. These types of projects may lead to high levels of concern from public, partner or stakeholders and Indigenous peoples in relation to the potential for adverse effects. DIA is the most intensive form of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) required by Parks Canada and may require evaluation of alternatives, expert advice, and development of a follow-up monitoring program. In addition this level of EIA requires public engagement and consultation, including:

- Notification from Parks Canada to relevant parties (the public, stakeholders, Indigenous peoples) of the decision to undertake a DIA for a project, and provide information on the planned EIA including a project summary, an overview of the valued components to be assessed, and an outline of planned review, engagement and consultation opportunities.

- Opportunity to review and comment on the draft DIA, at a minimum, is required (the opportunity to review the draft Terms of Reference for the DIA may also be considered, at the discretion of the Field Unit Superintendent/Director of a Waterway).

Original trail with boardwalk. Courtesy of Dennis Minty

July 2018 new trail. Courtesy of Michael Burzynski

Who’s Benefiting from the new Access Road?

Tourists: People visit Newfoundland and Labrador for it’s rugged beauty and untouched nature. Trip Advisor already shows negative comments from visitors about the Western Brook Pond trail. The path to the pond was previously not only used as an access point to the boat, but as a nature trail walked for pure enjoyment and for the vistas of the Long Range Mountains. That trail no longer exists.

Locals: Most locals take the boat tour once, if at all. After that, the trail is used primarily for hiking, bird watching, plant identification, and simple appreciation of nature. Now there is no reason to walk this trail except as an access point to the boat tour, meaning locals are unlikely to frequent the trail.

Parks Canada: Has worked tirelessly in recent years to form positive relationships with local people across the country. Their management plans clearly state that local consultation is of paramount importance. People lived in the Gros Morne area long before a park was established. Over the years locals have complained about the restrictions to access natural resources in the park, and fines have been issued for people violating the Parks Canada Act by using all-terrain vehicles, or harvesting natural resources. These changes to the trail represent a double standard for Parks Canada and locals, and a blatant disregard for the environment and for the opinions of the locals. It is going to damage already tenuous local relationships.

On a larger scale this is going to weaken Canadians’ trust in Parks Canada as the guardian of our national parks and heritage sites by potentially violating their own legislation and favouring the almighty dollar over the environment. It could also jeopardize the park’s status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Why is Parks Canada using public funding to enhance a private business?

Boat Operator: What kind of relationship does BonTours have with Gros Morne National Park? This does not look good on the company, as they have a responsibility here too. Tourism operators have to take ownership of the impact that their businesses have on the environment, especially when operating in a national park. The current tour is offered 6 times daily at a cost of $65 per passenger (not including park passes) and a boat capacity of 100. Based on customer numbers (40,000 in 2017), that generates approximately $39,000 per ride or $2.6 million dollars annually. This is big business, and the aim is to expand with bigger boats and facilities.

Last Word

This project is touted by the park as necessary because Western Brook Pond is the most visited site in the park. The webpage detailing this project states that “these expansions and upgrades will help ensure the quality and reliability of visitor facilities and continue to allow Canadians to connect with nature.”

Non-exhaustive List of Conflicts

- This is user-based decision-making in a national park. If the trail could not accommodate visitors, why not limit the number of visitors on the trail? The Parks Canada Act clearly states that the ecological integrity comes before use.

- If the park really was concerned about accessibility, why wasn’t the Coalition of Persons with Disabilities Newfoundland and Labrador consulted about the needs of persons with disabilities? In a CBC Radio interview, their representative calls this a “missed opportunity for park officials to reach out to the disability community and get a better understanding of what is best practice and what would really work for people who need that experience” (Nancy Reid)

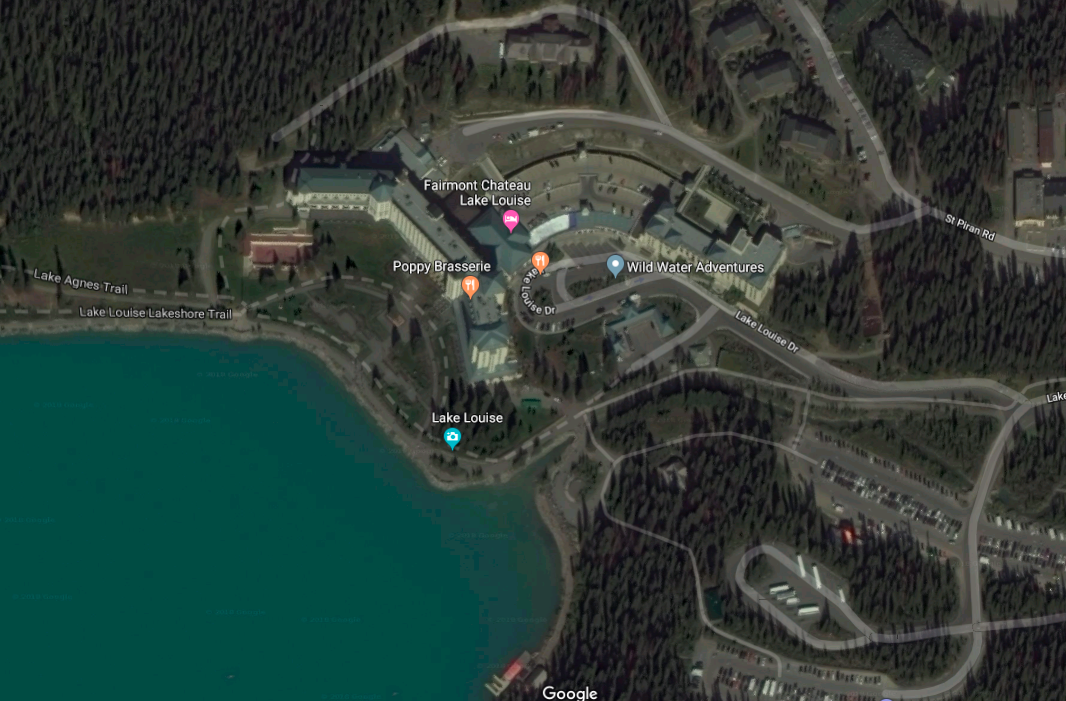

- Parks Canada has unilateral decision making power. The plan today is to dredge the pond for bigger boats, expand the parking lot by 50%, widen and flatten the trail, and to shuttle people from the parking lot. Are there any restrictions or protections to ensure that this does not become the next Lake Louise (Banff National Park), with a paved surface to water’s edge, and hotels overlooking the fjord?

Key Questions

- How does the park know that the ecological integrity of the ecosystem will not be affected by the new access road if a Detailed Impact Assessment has not been performed?

- Are there limits to construction in National Parks? How can Canadians ensure that Parks Canada doesn’t destroy natural heritage sites?

- Has the IUCN World Heritage Committee been consulted by Parks Canada, and how do they respond to the destruction of an iconic landscape in a World Heritage Site?

- Is there a carrying capacity / tipping point in these natural areas, where increased visitation to popular natural areas eventually destroys the very thing people are going there to see?

- How environmentally sustainable is it to have 40,000 people per year on the Western Brook Trail?

- How sustainable are six boat tours per day of 100 passengers in diesel-fuelled boats at the head of what has been listed as a sensitive tributary to the salmon river, Western Brook?

- What is the financial relationship between Parks Canada and BonTours, the boat operator?

Lake Louise, Banff National Park

Lake Louise satellite view of environmental footprint. Hotel, parking, paved surface around lake.

Taking Action

The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society has made a statement, and is requesting that Parks Canada

- Halt further road development into Western Brook Pond until a detailed impact assessment and thorough public consultation has been conducted;

- Publicly release all documents which detail what research, decision-making, and evaluation processes were conducted leading up to the onset of infrastructure changes at Western Brook Pond;

- Publicly release a detailed project list showing all projects being undertaken in Gros Morne National Park that utilize federal government infrastructure monies; and

- In the future, inform and involve local residents, visitors, and interested Canadians in development projects throughout the planning, development and construction phases.

HAVE YOUR SAY: SEND AN EMAIL!

- The Honourable Dwight Ball, Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador, and MHA for the park area: [email protected]

- The Honourable Catherine McKenna, Minister of the Environment and Minister responsible for Parks Canada: [email protected]

- The Honourable Gudrid Hutchings, Member of Parliament representing Long Range Mountains district: [email protected]

- Daniel Watson, CEO of Parks Canada Agency: [email protected]

- Geoffrey Hancock, Superintendent of Gros Morne Nat’l Park: [email protected]

About the Author